CoMo No. 24: Sweden (June, 2024)

Posted: Sat Jun 01, 2024 10:24 am

a place to talk about movies and whatnot

http://scfzforum.org/phpBB3/

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

1. Editors' Preface

Acknowledgements

I. Institutions

Changing Institutions for Film Screenings

2. Introduction / Mariah Larsson

3. Going to the Cinema / Kjell Furberg

4. Censorship in Sweden / Jan Holmberg

II. Silent Cinema

Introducing Cinema to Sweden

5. Introduction / Anders Marklund

6. Film Exhibition in Orebro 1897-1902 / Asa Jernudd

7. Georg af Klercker, the Silent Era and Film Research / Astrid Soderbergh Widding

Golden Age and Late Silent Cinema

8. Introduction / Anders Marklund

9. Victor Sjostrom and the Golden Age / Bo Florin

10. Selma Lagerlof and Literary Adaptations / Leif Furhammar

11. Travellers as a Threat in Swedish Film in the 1920s / Tommy Gustafsson

III. Genre Cinema

Popular Cinema in the 1930s

12. Introduction / Anders Marklund

13. Melodramas of Gustaf Molander / Bengt Forslund

14. 1930s' Folklustspel and Film Farce / Per Olov Qvist

15. Celebrating Swedishness Swedish-Americans and Cinema / Ann-Kristin Wallengren

Hollywood's Influence after the War?

16. Introduction / Mariah Larsson

17. Youth Problem Films in the Post-War Years / Bengt Bengtsson

18. Little Miss Lonely Style and Sexuality in Flicka och hyacinter / Mia Krokstade

Documentary Filmmaking in Sweden

19. Introduction / Mats Jonsson

20. Fly on the Wall On Dom kallar oss mods and the Mods Trilogy / Bjørn Sørenssen

Genre Filmmaking in a Difficult Film Climate

21. Introduction / Anders Marklund

22. Pippi and her Pals / Chris Holmlund

23. Criminal and Society in Mannen pa taket / Daniel Broden

24. Contested Pleasures / Mariah Larsson

IV. Auteurs And Art Cinema

Art Cinema, Auteurs and the Art Cinema `Institution'

25. Introduction / Mariah Larsson

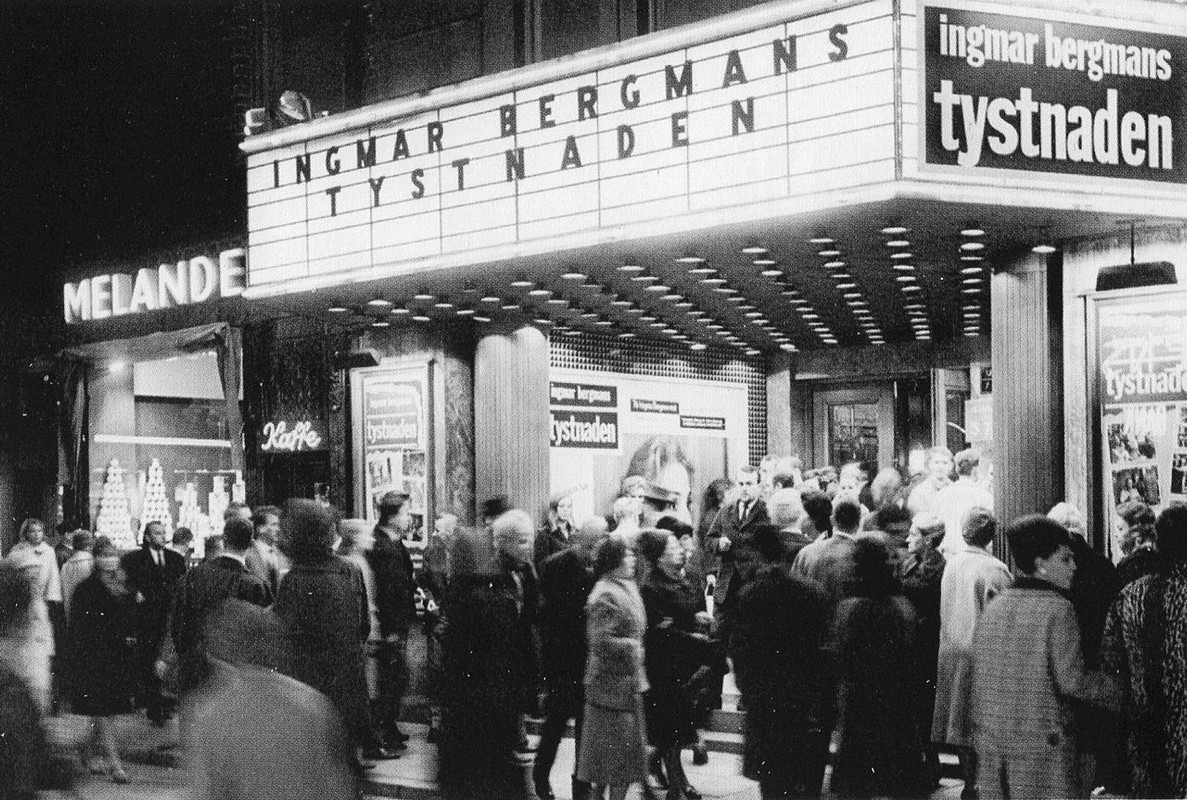

26. Ingmar Bergman and Modernity Some Contextual Remarks / Erik Hedling

27. Peter Weiss: Underground and Resistance / Lars Gustaf Andersson

New Generation of the 1960s

28. Introduction / Anders Marklund

29. Reception of Vilgot Sjoman's Curious films / Anders Wilhelm Aberg

30. Poetry in Sound and Image Jan Troell's Early TV Films / Johan Nilsson

31. Modernity, Masculinity and the Swedish Welfare State: Mai Zetterling's Flickorna / Mariah Larsson

Changing Conditions for Auteurs after 1970

32. Introduction / Mariah Larsson

33. Complex Image / Roy Andersson

34. Distinctive Films in Mainstream Cinema Suzanne Osten's Broderna Mozart / Anders Marklund

V. Before And After the New Millenium

Renewal of Swedish Film?

35. Introduction / Mariah Larsson

36. Distinctive Films in Mainstream Cinema Yrrol & Tic Tac / Anders Marklund

37. `Immigrant Film' in Sweden at the Millennium / Rochelle Wright

Swedish Films and Filmmakers Abroad

38. Introduction / Anders Marklund

39. Lasse Hallstrom: Family Secrets / Tomas Fernandez Valenti

Production and Producers

40. Introduction / Anders Marklund

41. Local and Global Lukas Moodysson and Memfis / Anna Westerstahl Stenport

42. Regional Turn Developments in Scandinavian Film Production / Olof Hedling.

since the last film that i watched for the previous CoMo was NEIGHBORHOOD CINEMASole dole doff wrote: ↑Sat Jun 01, 2024 1:03 pm Mariah Larsson & Anders Marklund - Swedish Film: An Introduction and Reader (2010)

3. Going to the Cinema / Kjell Furberg

Film and the cinema came to Sweden exactly six months later than in Paris, on 28 June 1896, arriving at the Industrial and Handicrafts Exhibition in Malmö. The venue was a theatre building in Moresque style, specially designed for the exhibition. It can be noted that the first cinema premises, not only in Sweden but also in Paris, were designed in an oriental or exotic style – and this would again be popular among Swedish cinema designers in the 1920s.

After 1896 the novelty spread throughout Sweden. Film exhibitors travelled up and down the country with portable projectors. They rented some suitable hall, such as temperance lodges, Free Church mission houses, theatre auditoria and soon even premises belonging to the labour movement. So, in fact, in these first years film was to a great degree a socially acceptable phenomenon. There were even touring tent cinemas, but these were not so common. Sometimes films were shown as part of a variety of circus performances. In Stockholm the breakthrough came at the General Art and Industry Exhibition on Djurgården, where the Lumières Kinematograf was run by Numa Peterson. The cinema was housed in a miniature medieval Stockholm setting.

When the exhibition closed in the autumn, Peterson’s son, Mortimer, continued to run the Lumières Kinematograf in a room with sixty-three seats at Kungsträdgårdsgatan 12. This was Stockholm’s – and Sweden’s – very first permanent cinema, but it closed down after ten months. The lack of new films meant that the incipient cinema fashion more or less died out. It was not until 1904 that Stockholm’s next permanent cinema was established: the Ideal. A few days later the third permanent cinema in Stockholm opened: the Blanch-Biografen.

The Dane Niels Le Tort played an important role as an entrepreneur in this pioneering cinema epoch: he opened Gothenburg’s first permanent cinema, situated in the Arkaden, in July 1902. Initially there was no projection booth – the projectionist and projector were under a cloth in the auditorium. In Malmö, too, Le Tort opened the city’s first permanent cinema, in August 1904: Malmös Biografteater.

Places where films were screened did not originally have their own names. Adverts emphasised the name of the projector, which gave us the first word for cinema: kinematografteater. The Royal Biograph was a brand name for a type of projector that Niels Le Tort used at the screenings in the Blanch-Biografer in Stockholm in 1903. He advertised biografföreställningar, i.e. biograph performances. The Royal Biograph was reputed to be a projector of the very highest quality. Other exhibitors started to advertise their biograf performances too, despite their having less reputable projectors. Within a year or so, the word biograf became the general term for a film projector, and – in a transferred sense – for a place where films were shown. The word biograf comes from the Greek: bios means life, and grafein means to draw or write.

Sweden’s foremost expert on the history of Stockholm cinema theatres, Olle Waltå, has noted that the word biograf was first used in a newspaper advertisement in Stockholm as early as 3 January 1899 – this was ironically for a film screening that was part of a circus performance. It was probably the name of the projector that was being referred to on that occasion. Initially, the rather elegant combination biografteater was the common term for a cinema. But already early in the century, people started to say simply biograf, which was soon shortened to ‘bio’. Only Swedish and Danish use bio and biograf as the words for a cinema; it is also used as a loanword in Icelandic, Faroese and Greenlandic.

Scala in YstadAround 1905 the first cinemas were built that were specially designed for showing films, but they were few in number. There was still an uncertain supply of films, and there was no domestic Swedish production until 1908. It was not until after 1910 that the building of cinemas really got under way, and the number of permanent cinemas in Sweden in 1911 was estimated at about 200. The oldest purpose-built cinema still intact and well-preserved today is the Scala in Ystad, opened in 1910. The oldest permanent cinema that was built in an existing building and is still showing films today is the Saga in Kalmar, from 1906.

Svea in SundsvallOne of the most interesting cinemas from the pioneering period is the Svea in Sundsvall, designed by the architect of Stockholm’s city hall, Ragnar Östberg, and opened in 1912. It is still intact today and in 1988 was the first cinema theatre to be classified as a building of special historical interest that should be preserved for cultural reasons.

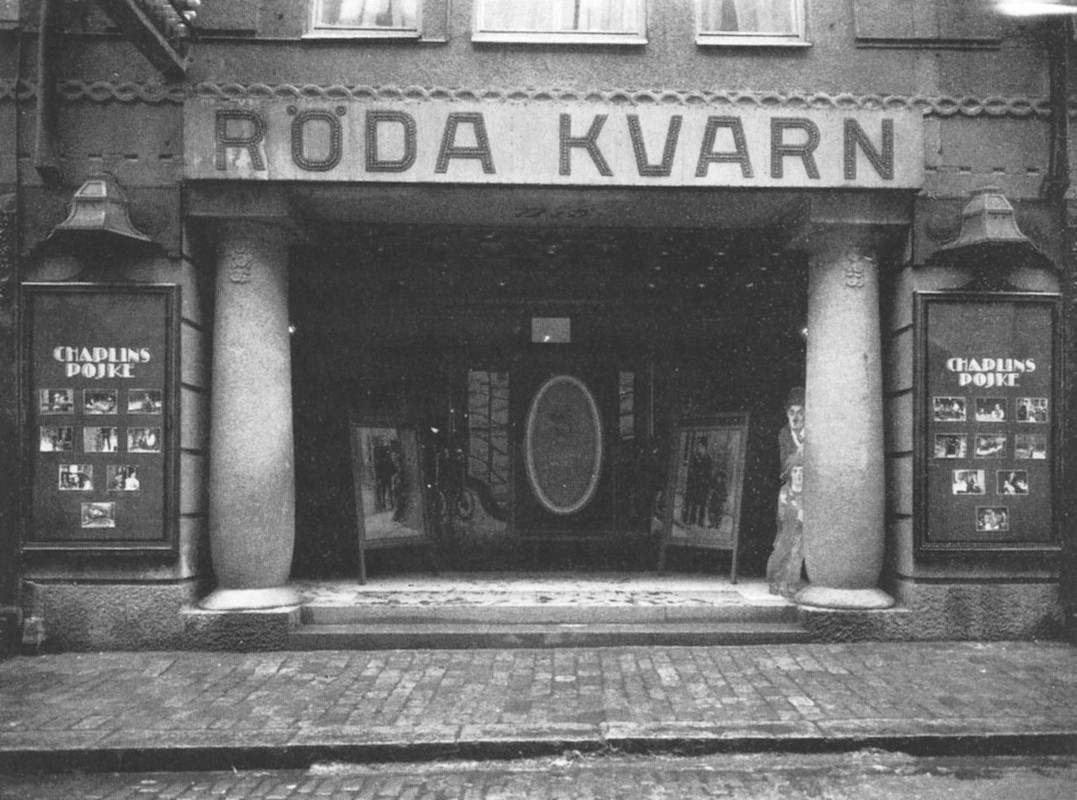

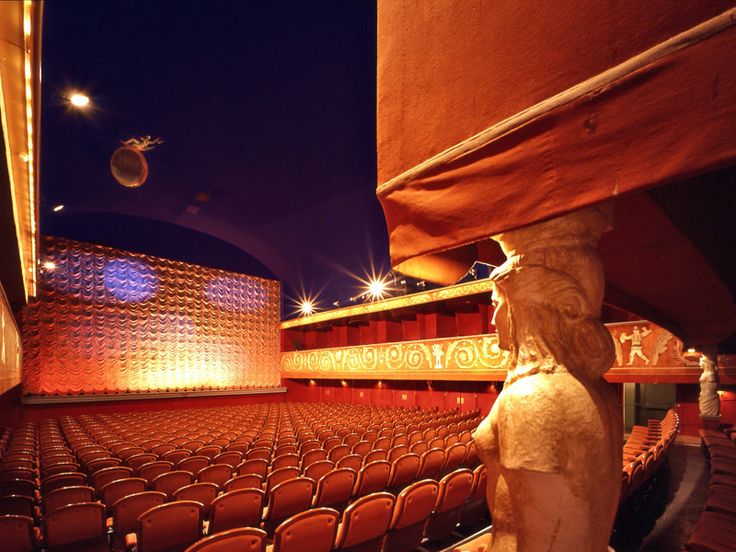

Röda Kvarn in StockholmA milestone in cinema history was the building of the lavish, artistically decorated Röda Kvarn in Stockholm, opened on 30 December 1915. Here was a surfeit of classical elements, works of art and luxury, and this cinema theatre came to be something of a model for the rest of the country.

Skandia in StockholmThe 1920s meant larger, palatial auditoria in Swedish cinemas, the largest of which seated almost 1500 people. Swedish neoclassicism made its breakthrough, and the interiors became lighter, more open and smarter – not nearly as overburdened as in the previous decade. It was popular to have a feeling of outdoors and various types of stylised firmaments on the auditorium ceilings. The most original cinema from this period is the Skandia in Stockholm, designed by architect Erik Gunnar Asplund and opened in 1923. The Skandia has long been famous throughout the world, and is still reasonably intact. In the late 1920s elements of art deco were gradually incorporated in the neoclassicism, and there were sometimes design features from ancient Pompeii, Greece and Egypt, as well as from China.

Draken in StockholmIn the mid 1930s cinema construction got under way again, and now a style was developed which, while based on functionalism, meant a little more decoration and cosiness. This funkis period was also the heyday of canopies with neon lights, which were a feature of cinema entrances until the end of the 1950s. The first neon signs were probably put up at the Sture in Stockholm in 1925. A warm degree of intimacy matched with a worldly elegance and comfort were characteristic of pre-war cinema style – luxury that contrasted strongly with the overcrowded and rather primitive housing conditions of most Swedes at the time. Perhaps the century’s artistic zenith as regards architecture, design and decoration was reached in the cinema building-boom, which lasted from the late 1930s until 1943.

With the advent of sound film a proper film screen became a necessity – the loudspeaker was placed in the middle behind the screen, which could thus no longer be painted directly onto the wall. The silent era convention of a centre aisle in the middle of the seating area was abandoned; after all, the best seats were in the middle, in front of the screen, as regards both sound and picture. Towards the end of the decade it became more common to build cinemas without a balcony, which meant that the stalls seating area could be sloped at a greater angle to provide a better view of the screen. The Draken cinema in Stockholm, from 1938, was seminal in that respect.

Bio Victor (364 seats) & Bio Mauritz (130 seats)Just after the mid 1950s, the same time that television started up, the audience figures for Swedish cinemas were the highest ever. And there were more cinema theatres than at any other time: about 2,500 in all. As a ratio of cinemas to population, this was a European record. This was in part due to the unique structure of cinema ownership in Sweden, with its many cinemas owned by popular movements. The temperance societies and the labour movement were quick to equip their lodges and folkets hus (community halls affiliated to the labour movement) with film projectors. It was a way of helping to finance other activities. It also meant a great deal for the spread of film and cinema culture and making it extensively available, not least in country districts. This type of cinema was seldom designed and fitted out purely as a cinema theatre. Instead it was often a question of an unglamorous hall with several functions: meeting hall, concert hall, theatre stage and auditorium, dance floor – and cinema.

Swedish television started broadcasting in 1956, and made its definitive breakthrough in 1958 with the World Cup in football. Most cinema proprietors stuck it out until about 1960. There were even some new cinemas built between 1959 and 1961. But by 1960 it was clear that the audience figures had declined drastically. Cinemas started to close down, and many were demolished. Those remaining were often subject

to irreverent renovation projects in the 1960s and 1970s, which often displayed even greater insensitivity than in the 1940s.

The Swedish Film Institute’s building Filmhuset (House of Film) with its three cinemas, the Victor, the Mauritz and the Julius (the references being to Sjöström, Stiller and Jaenzon), was designed by architect Peter Celsing and opened in 1971. This building was a purist’s expression of 1960s modernism in an independent, uncompromising manner, and he succeeded in creating a contemporary, yet unique building of the very highest artistic and architectonic quality. The Cinemateket film club screens films in the Bio Victor, but there are no public screenings in the Filmhuset cinemas. The Bio Victor is still one of Sweden’s best film auditoria, and when it was built it was ahead of its time, with its steeply sloping floor and large film screen.

i would love to end this post (to illustrate the overall doom) with a picture of the 1980s sickly-sweet (like a children’s nursery) interiors of the Filmstaden multiplex but i can't find any (lack of such a decadent picture means i am ending on a positive note).The first constructive idea for dealing with the competition from television came from Sandrews (an integrated film and cinema company). In 1970 the managing director of Sandrews invented the multi-screen cinema together with architect Fredrik von Platen. An old cinema was divided into three small auditoria and was reopened in 1970 as a multiplex cinema. It was hoped that if, in the same building, more films could be shown in auditoria of adequate size, then the cinema would become profitable again. This was conditional upon automated running which did not require more staff than the old single-screen cinema. At the same time the interior was adapted to suit modern times: simplification, reduction and standardisation were the order of the day. Decorative elements and curtains were removed, and all surfaces were painted in red and black.

In the 1970s Sandrews continued to ‘butcher’ and remodel old cinemas throughout the country, and they even started to build new multi-screen cinemas. These new multiplexes were often sited in basement premises, which meant lower rental costs. Sandrews’ multi-screen investment was an emergency solution, but it was successful from a financial point of view and meant that while many older cinemas were admittedly largely destroyed, despite everything they were not closed down.

Exactly ten years later, in 1980, Svensk Filmindustri opened their first major multi-screen project: the Filmstaden in Stockholm. This had a great deal in common with Sandrews’ multiplex cinemas: the small, curtainless auditoria, rather small screens and floors that did not have a sufficient gradient. There were, however, more auditoria than at Sandrews: at first eleven, which later became fifteen. The decoration and atmosphere were more varied than in Sandrews; in Filmstaden it was designed by the idiosyncratic interior designer Lennart Clemens – although rather sickly-sweet like a children’s nursery with pastel shades and patterns.

Baboona was a hit in Röda Kvarn in 1935!

wow what an amazing couple. i'll try to visit their museum next time i'm driving across kansasMartin and Osa Johnson

Ulla Billquist became the leading star of the Second World War era in Sweden. She toured throughout the country, singing for soldiers wherever they were billeted.

Ulla Billquist secretly frequented bi- and homosexual artistic circles. She was also part of a women’s network in which the women all took male names – Ulla was knows as “Olle”, Kai Gullmar was known as “Kungen” (the king), and Zarah Leander was called “Alex”. The reason for the secrecy was that homosexuality was illegal until 1944 and thus it is highly likely that Ulla Billquist was the subject of blackmail. She and her daughter Åsa both expressed that finances were tight although they lived simple everyday lives whilst benefiting from an advantageous record contract and many well-paid performances.

On 6 July 1946 Ulla Billquist committed suicide. Three years later her friend Hasse Ekman produced the film Flicka och hyacinter (1950) which was inspired by her life. Hasse Ekman’s anonymous tribute comprises a captivating description of a sensitive artistic soul and her death which comes as the result of a homosexual love affair. He was ahead of his time with his portrayal of homosexual love as pure and beautiful, while the male heterosexual singer in the film is depicted as a morally loose man who sees a different woman every day.

In Stockholm in the year 2248 an excavation leads to the discovery of 45,000 meters of film from the 1940’s master director Hasse Ekman. The material is in a disarray but the Society for Ancient Film Research compiles the material after what is believed to have been the master’s artistic intentions.

a precursor to CAN DIALECTICS BREAK BRICKS?

https://www.solarisfilm.se/portfolio/gr ... ectations/

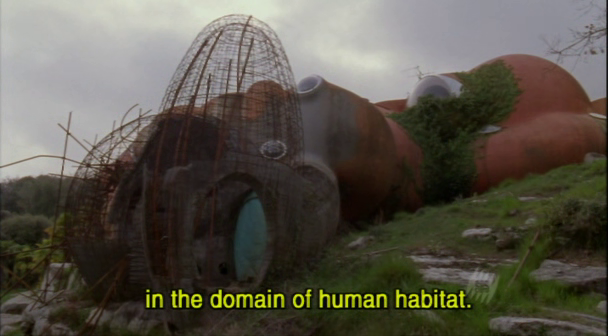

This documentary provides an astonishing journey through innovative, futuristic, utopian, and sometimes bizarre architecture projects — including concrete illusions of grandeur and Lego-like modular apartments to an Instant City Airship and round, grass-covered subterranean dwellings — from the beginning of the 20th century to today.

LE GÉNIE CIVIL (Claes Söderquist, Jan Håfström, 1967) #CoMoSverigeIn Söderquist’s first film In Tuxedo, playfulness and improvisation are combined with absurd humor.

An artist steps into an empty studio and begins assembling objects into a tree-like sculpture. The sculpture is adorned with small white paper clouds, puppets and undefinable items; all the while, the studio fills up with new things: a suitcase, a mirror and formal attire.

The artist, now wearing a top hat and tuxedo, paints the paper clouds and the wall in a frenzy of activity, ending with his sitting exhausted in a corner surrounded by the mess he has created.

The growing chaos, the various layers of narrative and the music of the soundtrack, which was improvised and recorded live during a viewing of the final film cut, interact in counterpoint.

LANDSCAPE (Claes Söderquist, 1987) #CoMoSverigeLe génie civil consists of numerous etchings and photogravure prints from an engineering journal, illustrating the advancement of industrialism in the late 1800’s.

The filmed illustrations are allowed to speak for themselves as still images during a prolonged cinematic time, a kind of viewing time. In a reciprocal and dense interaction with a collage of noise from trains, rain, thunder, a ticking clock and organ music, the material is brought to life and the narrative of the film slowly emerges.

Because the images in Le génie civil are taken out of their original context and placed in another time and space, they link the past with an ongoing present.

Landscape is Söderquist’s first minimalistic film. Together with Passages – Portrait of a City (2001) and Labyrinth (2013), it forms a trilogy exploring space by means of the landscape and the city. The slow camera shots show the inertia of nature and the temporality of thoughtfulness.

The film is cut in motion to give a coherent structure of movement, a kind of course of events, through a multifaceted landscape of rich ferns, swaying treetops, winding roots alternated with reflections in a rippling stream. Landscape is a focused and tightly formed panorama, whose masterly projection of natural sound and cyclical construction are manifested in seasonal color- and light variations and in flowing water.

SCORE (Katarina Löfström, 2004) #CoMoSverige

Troell, his collaborator Forslund, and Clas Engström, on whose 1957 novel the film is based, were all former teachers, but this is no recruiting poster.

Shot in Troell's old school in Malmö with compact 16mm equipment and minimal crew, it's a story of disintegration, boasting a brilliantly nervy central performance from Bergman regular Oscarsson as a teacher who oversteps the mark in trying to retain control of his rowdy pupils. It's a sign of his insecurity, a product (yet also a cause) of his wobbling marriage, but the kids can see the fear in his eyes and the confrontation escalates.

Gerd Osten was one of Sweden’s leading film critics in the 1940s and a representative of a new, younger generation of writers who wanted to make their mark on Swedish film. From an early age she was fascinated by European film and how it influenced contemporary Hollywood film: French film noir, for example, and German expressionism, with its dark imagery, its acting that highlights powerful emotions and its sophisticated exploration of symbols and stereotypes.

Osten wrote film criticism in BLM, Dagens Nyheter and the magazine Vi under the moniker “Pavane”. Her film criticism has been collected in four volumes: “Det förlorade paradiset: essäer om film” (‘Paradise Lost: Essays on film,’ 1947), “Erotiken i filmen” (‘Eroticism in Film’ with Artur Lundkvist, 1950), “Nordisk film” (‘Nordic Film,’ 1951) and “Den nya filmrealismen” (‘The New Realism in Film,’ 1956).

The story of her mother’s struggle to make films, Suzanne Osten’s film is in many ways the film that Gerd Osten wanted to make: a romantic adventure with a strong woman lead.

but at that time – Sweden in the early 1940s – there was no forum for female creativity of this kind. And yet she carries on working on her screenplay and gets various pieces of advice from a male director named Bosse: write a proper ending; get some experience; work as a script supervisor on my film.

Bosse is a low-key portrait of Ingmar Bergman, and Osten was indeed the script supervisor for his film The Land of Desire (Skepp till Indialand, 1946, US title: Frustration).

Of the few films that Gerd Osten made only three have survived. In two short films she documented some of the most legendary figures of Swedish dance: Birgit Cullberg and Julius Mengarelli in Antonius och Cleopatra (‘Antony and Cleopatra,’ 1948), and Topsy Håkansson in Zigenardans (‘Gypsy Dance,’ 1948). The third is the short Ung kvinna (‘Young woman’), which may have been part of her proposed feature film, about a young woman waiting for her lover who subsequently metes out a sophisticated punishment on him after they have made love. This short film was screened in cinemas in 1954, surprisingly enough as part of an everyday newsreel.

btw. the English title OUR LIFE IS NOW (orig. Ole Dole Doff, literally something like "eeny, meeny, miny, moe") is the words of wisdom by Prévert (by a subversive subtitler called Pervert)In an essay on amateur filmmaking in Sweden between 1930 and 1965, film expert Mats Jönsson reveals that in 1938 a Swedish filmmaker named Gerd Baeckström took the short fictional film David to a film festival in Budapest for which she won the festival’s third prize. The following year, at a short film festival in Zürich, Baeckström took part with a film entitled November. Jönsson maintains that Gerd Osten and Gerd Baeckström are one and the same person, establishing her as part of the early, artistically-ambitious wave of Swedish short film production. Unfortunately neither David nor November have survived.

↓↓↓ autotraslated (Bengt Forslund, 2015) → https://www.filminstitutet.se/sv/fa-kun ... d-prasten/

A newly graduated elementary school teacher (Viveca Lindfors) gets a job in a small rural parish where she has difficulty accepting conservative values and begins a relationship with the priest (Georg Rydeberg).

Few novel debuts have caused such a stir and reached such a large readership as Ester Lindin's Tänk, om mej mej mej mes presten. It was not due to the literary qualifications and only partly to the fact that it won first prize in one of Hökerberg's publishers' novel award competition about "the professional woman of our time". The main reason was that many felt that the teacher in the film was too liberated and a bad example for her profession.

Ester Lindin was herself a primary school teacher and the book was her only success. Whether it was partly autobiographical has never been revealed.

It is significant, however, that the depiction of the environment and people feels lived in and genuine, and that was something that the director Ivar Johansson (1889-1963) took advantage of.

Johansson is an unfairly overlooked director who played an essential role in Swedish film life for decades. He began as an editor, editor and screenwriter for a number of notable films during the silent film era (among others The Girl in a Coat, Karl XII, A Perfect Gentleman ) and in 1928 made a sensational debut with the Russian film-inspired Rågens rike — also the then overlooked sound film at the same time broke through.

His production during the 30s is, for better or worse, representative of the decade. Traditional entertainment films were mixed with time-conscious and realistically rooted films. Dismissed (1934), depicting the economic recession and unemployment, Burns (1935), and Storm över skaren (1938) were films that connected with Victor Sjöström's Terje Vigen (1917) and the Lagerlöfs films.

In both of the latter, single women with children play a not insignificant role, so the theme of "Tänk, om..." was not unfamiliar to him and it was just as obvious that Johansson was on the women's side when the slander and gossip started.

In "Think, if..." it was also about two different cases. A revivalist preaches to a young girl with a child and in her despair she kills the child. The teacher goes away and gives birth to her child after the priest leaves her, but defiantly returns to her position. Both women in the film, Gudrun Brost and Viveca Lindfors in the title role, received good reviews. For Viveca, the film was her definitive breakthrough on the big screen. The fact that she and Georg Rydeberg were also a couple in real life also helped.

Ivar Johansson continued his fight for women's rights in the Yellow Clinic (1942), a film about a women's clinic where women who want abortions are taken care of, also a controversial subject, and Ta hand om Ull a (1942), which depicted a young unemployed couple who want an abortion when the woman becomes pregnant. It can be said that Johansson stood out here as one of our leading portrayers of women on film, above all when it came to women in a vulnerable situation.

Both films were produced by the newly started Lux film, which got off to a successful start with these films. Lux-film had been formed by about 20 cinema owners who, during the war years, wanted to secure their own repertoire.

↓↓↓ → https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/If_I_Coul ... e_Minister

The novel by Ester Lindin which forms the basis of the film was already very controversial, and when it was announced that it would be adapted for the screen, a delegation of priests petitioned the film company Luxfilm and demanded that filming be stopped.

The chief executive officer issued an unofficial warning.

Despite this, the film was made and became one of the greatest successes of the 1940s.

One reviewer at the time wrote: "Since her novel was released [Ester Lindin] has had the questionable pleasure of getting pilloried in cheap cabarets and causeries as the amorality priestess number one. The film gives all these moral busybodies an answer that should sting — never before has moral hypocrisy and the false idyll of the philistine been exposed to such a mighty attack."

oh, cool! thanks!greennui wrote: ↑Thu Jun 20, 2024 5:19 pm I discovered an avant garde short made by Suzanne Osten's mother Gerd recently, randomly tucked away in a newsreel film

https://letterboxd.com/film/young-woman-1954/

https://www.filmarkivet.se/movies/nuet- ... pril-1954/