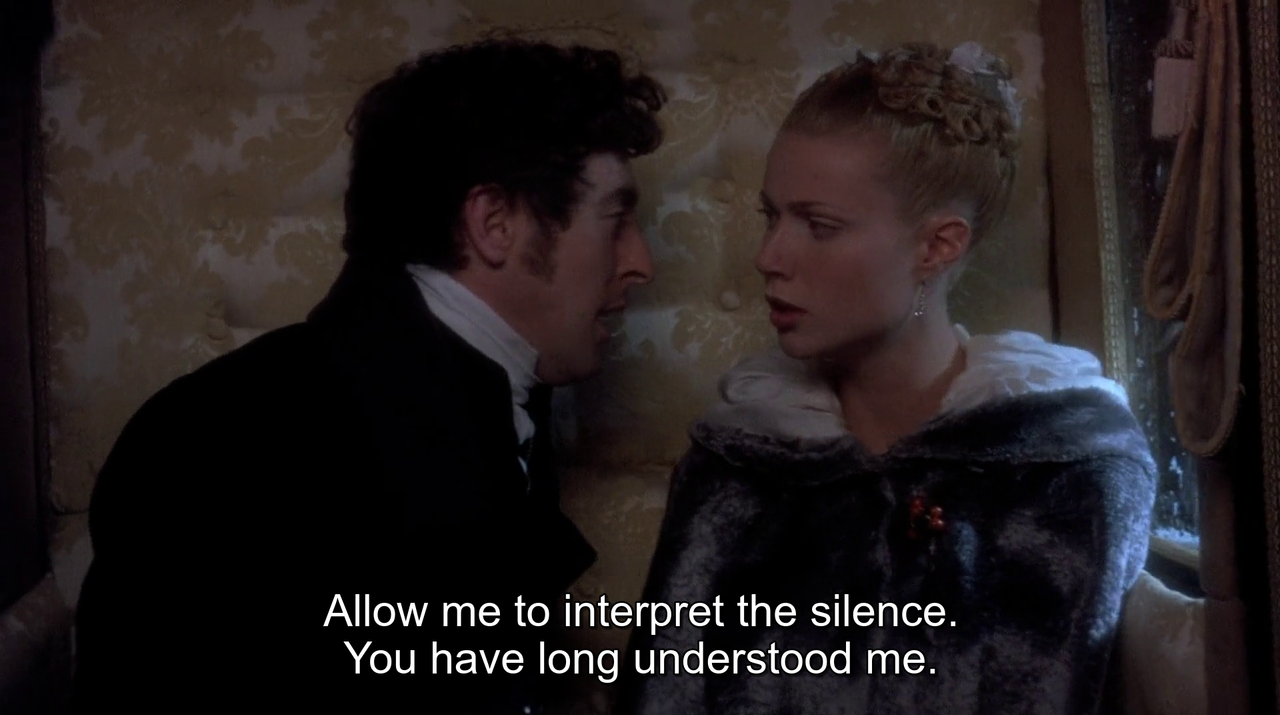

SENSE AND SENSIBILITY (Ang Lee, 1995) #CoMoGBakaUK

[Eavesdropping in the Novel from Austen to Proust, 2003]

The word “eavesdropping” implies placement of a listener in space. “To eavesdrop” originally meant to stand within the “eavesdrop,” or the space under the eaves of a building likely to receive rainwater from the roof. The word contains within it the concept of being near a private space (a house) and its secrets, and suggests a punishment for being so positioned; a person in the “eavesdrop” is likely to get wet. From this spatially oriented locution, which places an individual next to but not within an enclosed, protected space, eavesdropping comes to mean to listen secretly to the private conversation of others. The evolving meaning of the word changes from a physical encroachment on tangible private property to a metaphoric intrusion on psychological and discursive space. Eavesdropping suggests a particular sense of space: one that indicates boundaries of public and private areas, and transgressions of the former into the latter. It represents liminality: not being fully a part of the private world, but somewhat protected, while still part of the natural and public world. In its very demarcation, this border state presupposes the trespass of another individual’s sense of private space. Such transgressive activity usually carries with it the threat of danger or physical injury to the trespasser. Illicit acts usually do not go unpunished. In other languages, the locutions for eavesdropping also register the idea of location vis-a-vis privacy or domestic space, although in a less precise manner than in English. The German lauschen, meaning “to listen, strain one’s ears, prick up one’s ears, eavesdrop,” offers an adjectival form lauschenig, which means “snug, cozy, idy llic; hidden, tucked away,” and intimates a listening in on a space that is apart from a public area. The Russian pod slushivanye (literally, “underlistening”) etymologically positions the eavesdropper in a hidden space close to the speakers. Polish contains two locutions to express overhearing: podsluchiwanie and przysluchiwanie, where the former implies a transgression of privacy (being underneath the private conversation) and the latter a less morally weighted and less clandestine listening, usually in a semipublic place (the preposition przy meaning “next to” or “beside”). The French and Italian expressions for and prohibitions against eavesdropping, while not stressing a domestic environment, often indicate a proximity to walls or doors, structures that separate one space from another or regulate the passage from one to the next. These expressions include “les murs don't des oreilles;” “écouter aux portes;” “origliare alla porta;” “i muri hanno orecchie.” Other locutions are even less spatiallyprecise and articulate overhearing as “surprendre une conversation,” “etre aux écoutes,” or “ascoltare di nascosto,” “udire per caso, di nascosto.” In Spanish, the expression emphasizes the quality of being hidden: “escuchar a escondidas.”

The configuration of individuals and flow of information presented in eavesdropping are not exclusive to the novel. Indeed, eavesdropping plays a central role in drama from classical Greek tragedies through Shakespeare and eighteenth-century French and British comedies.

As the pun in its title suggests, Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing (1598) is constructed almost entirely around scenes of deliberate and inadvertent overhearing or “noting.”

Bakhtin perceives the centrality of eavesdropping to the genre of the novel and bases this recognition on the paradoxical correlation between its subject matter (private life) and a narrative transgression of privacy and private spaces. He asserts, “The literature of private life is essentially

a literature of snooping about, of overhearing ‘how others live’ . . . What matters are the everyday secrets of private life that lay bare human nature – that is, everything that can be only spied and eavesdropped upon.”

A wide variety of novelists from the English and French literary traditions represent narrative activity in a manner that confirms Bakhtin’s statement. Samuel Richardson has been disparaged for his “keyhole view of life,” by which he discloses to his readers the intimate aspects of his heroines’ individual experiences.

In the nineteenth century, the eavesdropping scene comes into its own as the flow of information — in novels and other media — accelerated. During this period, social, technological, and economic structures developed that fostered communication and produced a transfer of news from one body — individual, social, political, or economic — to another. Such changes transformed the experience of daily life in the nineteenth century.

By making information more available to a larger public, institutions such as the penny post, the telegraph, and newspapers transformed local events into potentially national knowledge.

Although the division of public and private spheres of activity emerged earlier, it is in this era that the desire to distinguish between the two became keenly felt, in part because “the rise of publicity. . . changed the significance of privacy and created a real or imagined need for secrecy.” The creation of an information society brought with it an anxiety about public opinion and placed an increased value on the notion of “discretion.”

Moreover, in a period that witnessed vast migrations to cities, social experience itself changed. People were in closer proximity to unknown others. Physical propinquity coincided with psychological mystery, producing both curiosity and opportunity to learn about others, as well as desire to shelter one’s own private life from them. Social mobility in general increases publicity, which in turn produces the greater desire for and value of privacy. Those who could afford to do so tried to protect private life through either the organization of living space or retreat to the suburbs or the country.

Eavesdropping produces narrative complication.

It figures not only the desire for secret knowledge but the multiple uses to which information maybe put, and the many stories generated, from an originary moment of overhearing. Episodes of secret listening mobilize or redirect narrative energies. They engender situations such as misunderstandings, partial hearings, or incorrect scenarios that require narrative to explain or account for them.

A character often overhears only part of a conversation and makes erroneous assumptions about the situation and the individuals it concerns. This causes a misunderstanding that may require the length of the narrative to resolve.

Even if overheard information is accurate, its secret appropriation almost always alters the course of the story and encourages narrative dilation. Alternatively, by providing information otherwise unavailable to characters and thus correcting misunderstandings or solving mysteries, eavesdropping can produce narrative closure.