80's gay alphabet...

also... being English = being water-soakedWhat’s at the bottom of being English? Perhaps the answer is: No!

Utopia is the past,

not the past as a golden age

but the past as ruins

of its own wounds.

Unrepeatable.

With recreation can come about

with a reverse of temporal flow

tempered by thermodynamics

to an entropy.

Entropy moving backwards

against itself

Received from us

we harness time to erect our utopias

Ruins of ruins,

tending so soon to dust

we labour in the warm days

to piece them back together.

And on the cold and howling days

new holes are bored

into the faith of the past.

We return and rebuild

another possible articulation.

If an equation is traced

depending on the slope

of selected tangents to the asymptotic

it is taken

as a direct sexual proposition.

Doneee.

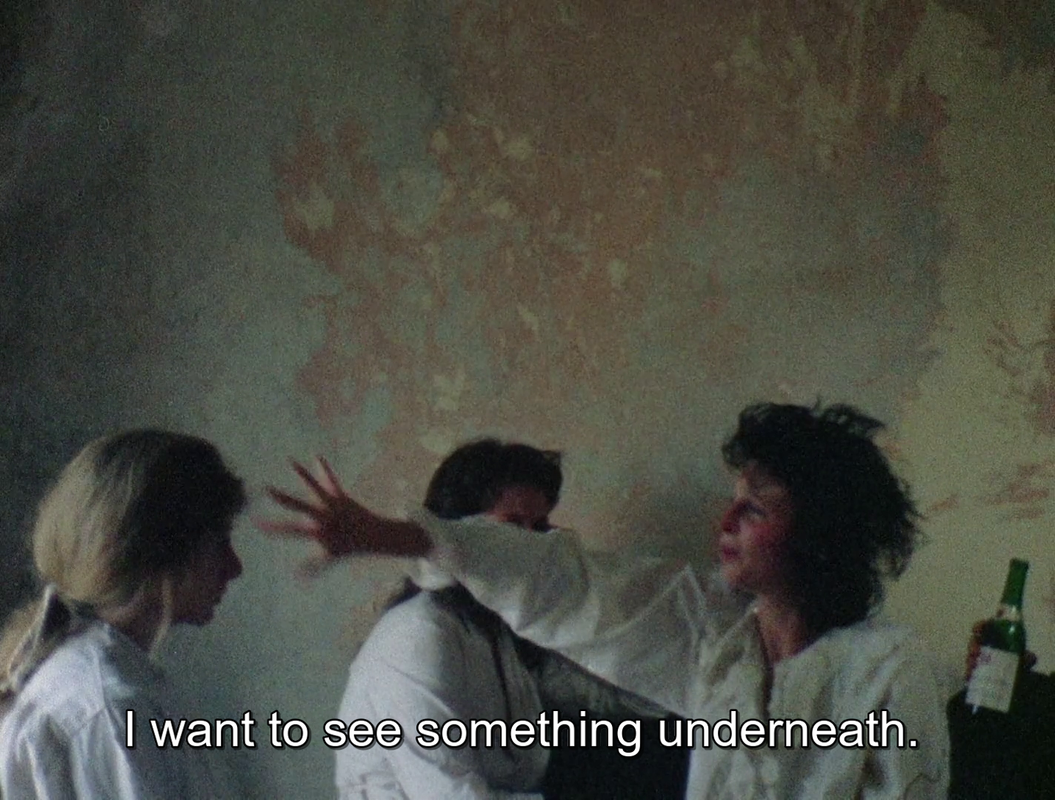

In 1970, artist Penny Slinger joined the radical feminist theatre troupe Holocaust, led by Welsh playwright and actress Jane Arden. Their debut production, A New Communion for Freaks, Prophets, and Witches (1971), became the basis for Arden’s 1972 film The Other Side of Underneath, a transgressive avant-garde opus that had Slinger in the dual role of performer and co-art director.

Made in 1972, Jane Arden’s The Other Side of Underneath was the only British film of the decade to be solo-directed by a woman.

more → https://cleojournal.com/2019/08/23/femi ... nderneath/

According to biographer Donald Spoto, Hitchcock was thoroughly bored by the project but entertained himself with one particular shot.

In the climactic scene, Chloe, played by Phyllis Konstam, attempts to drown herself in a garden pond.

Hitchcock, with characteristic cruelty, made the actress shoot the scene — and be thrown into the water by his stage hands — a full ten times.

In the end, the shot didn't even make it into the completed film.

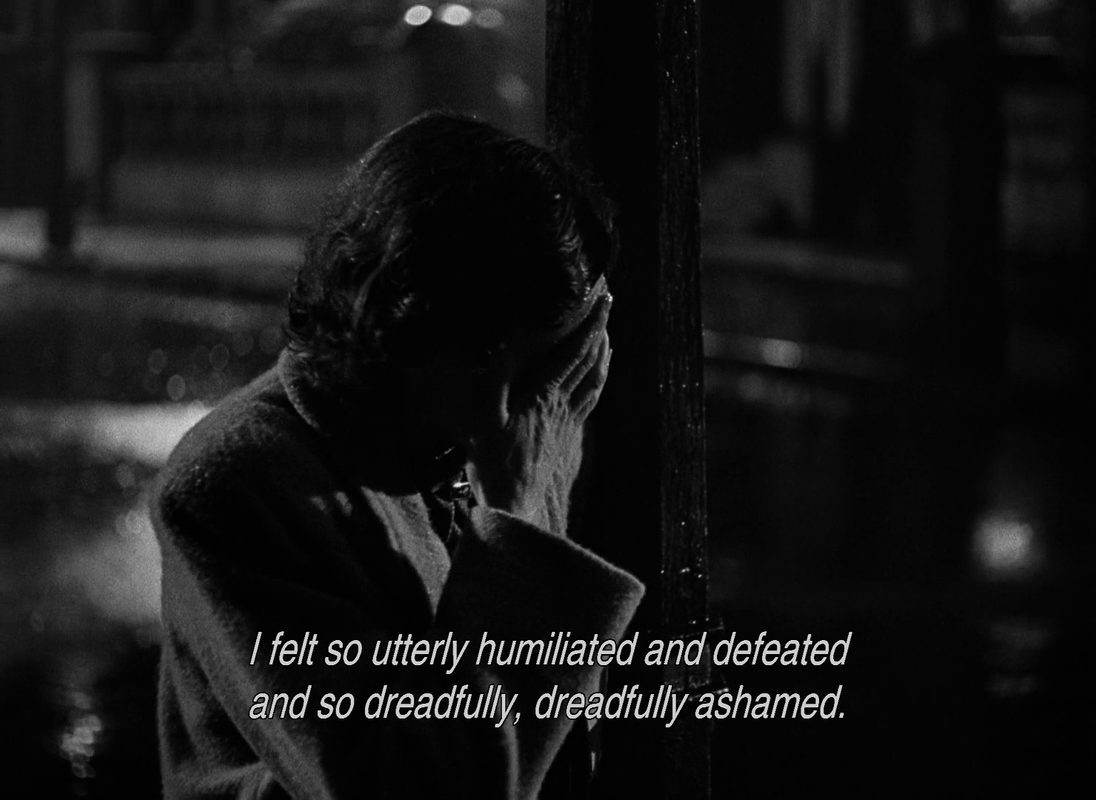

“What’s at the bottom of being English? Perhaps the answer is: No! A prohibition, an inhibition, far from wholehearted but generally observed.”

a staggeringly profound and far-reaching portrait of a nation, touching on everything from an apparently intrinsic desire for dominance, an inescapable individualism, industrialisation and its effects on workers, imperialism and its discontents, inequality, the fear of all things sensuous, and even the effects of sexual repression.

In a biography of David Lean, film historian Kevin Brownlow recalled an incident where an angry man stepped up to Lean at a railway station in London and declared that he had the urge to hit him and was holding back.

“Do you realise, sir,” he told the filmmaker, “that if Celia Johnson could contemplate being unfaithful to her husband, my wife could contemplate being unfaithful to me?”

→ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carnforth_railway_station

Carnforth Station Heritage Centre is the famous setting for David Lean's film Brief Encounter. This once significant railway station is situated at the junction between the main London-Glasgow line and the Carnforth-Leeds line, and the starting point of the Carnforth-Barrow-In-Furness line and a branch line to Morecambe.

The station has been lovingly restored and is now an award-winning heritage centre and unique conference venue.

The tea rooms have been restored to resemble the set used in Brief Encounter and now serve refreshments daily, while the extensive heritage centre tells not only the story of the making of the film, but delves into the history and heritage of Carnforth, its workers, and its families.

Watch Brief Encounter in our vintage mini cinema complete with tip-up seats.

Mazzetti’s debut film dispenses with all artifices to portray the original allegory (a man who turns into an insect), instead focussing on the alienation produced by society’s rigid expectations, which are here internalised and invisible.

On learning that the short film had been shot with material stolen from the Slade School of Fine Art (London), the rector of the department decided that its reception by an audience of teachers and students would determine whether or not Mazzetti should be expelled. Thankfully, the film received immediate praise from those present.

The phrase "ungeheuren Ungeziefer" in particular has been rendered in many different ways by translators.

These include:

"gigantic insect" (Willa and Edwin Muir, 1933)

"monstrous kind of vermin" (A. L. Lloyd, 1946)

"monstrous vermin" (Stanley Corngold, 1972, Joachim Neugroschel, 1993, Donna Freed, 1996)

"giant bug" (J. A. Underwood, 1981)

"monstrous insect" (Katja Pelzer, 1915, Malcolm Pasley, 1992, Richard Stokes, 2002)

"enormous bug" (Stanley Appelbaum, 1996)

"gargantuan pest" (M. A. Roberts, 2005)

"monstrous cockroach" (Michael Hofmann, 2007)

"monstrous verminous bug" (Ian Johnston, 2007)

"some kind of monstrous vermin" (Joyce Crick, 2009)

"horrible vermin" (David Wyllie, 2011)

"some sort of monstrous insect" (Susan Bernofsky, 2014)

"some kind of monstrous bedbug" (Christopher Moncrieff, 2014)

"large verminous insect" (John R. Williams, 2014)

A queer, psychedelic portrait of a young man’s desires in an industrial wasteland, this film by Paul Bettell contrasts tenderness of two men together with sequences of cranes and high buildings, and the piece builds to a transcendental and intense conclusion.

Filmmaker Bettell sadly made only two films before dying from AIDS-related complications.

Jane Austen wrote Persuasion, her last completed novel, between August 8, 1815, and August 6, 1816. During the summer of 1816, she began to feel ill of the disease of which she ultimately died, at the age of 42, on July 18, 1817. Many have speculated that the emphasis on the autumnal setting and on the aging twenty-seven-year-old heroine reflects the mood of Austen at that time and her awareness of her own unmarried situation.

Jane Austen has been praised as a master of social description, and in this essay [Narrating Multiple Realities: Some Lessons from Jane Austen for Ethnographers, 1984], we ask, “What would ethnographic narration be like, if Jane Austen were accepted, belatedly, as an ancestor?” We argue that Austen’s narrative technique skillfully interrelates diverse viewpoints, thereby presenting not an objective account of “the social system,” but the meaningful relations of myriad social realities.

By reading Austen, we can learn the subtleties of a range of understandings of experience, precisely because her texts are made up of lively interaction of many differentiated viewpoints, no one of which is allowed to obliterate the others.

The central characters of Austen’s narratives repeatedly face the problem of interpreting and judging potential spouses, and Austen’s readers engage in the parallel interpretative task of anticipating and judging the potential marriages considered by the characters.

If a new, unattached character is introduced in one of Austen’s texts, both the other characters and the reader soon ask, “Where in the scheme of things could this new person fit?”

The texts give no single answer.

On the contrary, Austen shows that the criteria for evaluating prospective spouses, and for judging marriages retrospectively as well, are multiple and partially contradictory.

Most generally, Austen’s texts reveal a sharp contrast (as well as the implicit relations) between “utilitarian” and “romantic” standards for evaluating marital unions.

In the simplistic vision of the most conventional characters, these criteria should produce a single interpretation of a character’s suitability as a spouse, but practice is not ideal in Austen’s novels.

Contradictions between a character’s nature as represented by his or her wealth, on the one hand, and the same character’s nature as represented by his or her personal traits, on the other, cause extreme difficulties in finding a partner who equally meets both standards.

do u love pride and prejudice but wish there was more industrial revolution and death? then boy do i have the BBC series for you!!

If someone had told me years ago that I would find myself watching the 2004 BBC television adaptation of Elizabeth Gaskell’s 1855 novel, let alone purchase a DVD copy of the miniseries, I would have dismissed that person’s notion as inconceivable. I have never shown any previous interest in ”NORTH AND SOUTH”. And I am still baffled at how I suddenly became interested in it.

[The Ethics of Risk in Elizabeth Gaskell's "North and South": The Role of Capital in an Industrial Romance, 2014]

The cultural shift in attitudes toward risk in the 1850s — specifically, the emergent need to avoid risk — is marked by the passage of limited-liability legislation such as the Joint Stock Companies Act of 1856 and the continuing rise of the insurance industry. Individual investors were no longer required to bear the losses of corporate failure, while insurance companies relied on the aggregation of both capital and information to calculate and compensate risk for the individual. Risk was to be managed by an impersonal collective in order to protect the individual from bearing any of its damaging consequences. Elizabeth Gaskell’s novel North and South (published serially in Household Words from September 1854 to January 1855) enters the discourse of mid-Victorian risk by articulating a vision of economic activity that takes the acceptance of risk rather than risk management as its central ethical precept.

Margaret Hale’s and John Thornton’s decisions regarding whether or not to invest their capital in particular enterprises demonstrate the persistence of an older understanding of ethical financial practice in which individuals must be willing to risk loss and bear the responsibility for such risk rather than asking others to do so for them.